The National Multiple Sclerosis Society is up to date on UConn Health’s MS research following a recent visit with biomedical students and faculty. One of the students, Brittany Knight, shares her account of the meeting.

Graduate students and postdoctoral fellows in the Neuroscience and Immunology departments used a variety of models and techniques to identify molecules that can improve myelination and ultimately provide therapies for those diagnosed with MS.

Myelination is when cells in the nervous system called oligodendrocytes produce myelin, a fatty substance that coats neurons and enables the fast transmission of electrical signals throughout the nervous system. Myelin is extremely important for everyday function including motor coordination (i.e. walking), sensory perception (i.e. eyesight), and thinking (i.e. remembering where you left your keys). MS causes myelin loss, which increase fall risk, impair vision, and lead to physical disability requiring a wheelchair.

One student shared is using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) derived from patient-specific brain cells to screen potential drugs. Another student is harnessing the power of the body’s microorganisms to preserve myelin using an animal model of MS.

Backed by a recent National Multiple Sclerosis Society grant, UConn Health neuroscience faculty members David Martinelli and Stephen Crocker are studying the myelin-producing cells.

“We are studying whether a signaling protein expressed by oligodendrocyte progenitor cells initiates a previously unappreciated signaling pathway that can lead to the maturation of oligodendrocytes,” Dr. Martinelli said. “This could potentially lead to a therapy for MS patients to replace lost oligodendrocytes.”

Another NMSS grant is funding a research collaboration between the Neuroscience Department and UConn Center on Aging, led by Dr. Crocker and assistant professor Rosaria Guzzo. They are examining the effect of aging on the “regenerative capacity of the brain in MS using iPS cells that were generated from progressive MS patients,” Dr. Crocker said.

The Crocker lab previously has shown that cellular aging, or cellular senescence, is an active process in MS that may open new therapeutic opportunities to stimulate brain regeneration.

Although MS is a debilitating disease, most people who have it do not develop severe disabilities and can appear unaffected. One of the discussions during the visit was about the challenges of living with MS.

It was stressed that MS, unlike other conditions, is not an obvious condition from an individual’s mere physical appearance. This can create discord between the public perceptions of a person diagnosed with MS and the reality of the disease. For example, myelin loss can cause people to have poor control over their gait or body, which can appear similiar to being under the influence of alcohol.

Current treatments for MS are a tale of the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The good news is, treatments for MS have change drastically over the past 10 years. There are now at least 12 disease-modifying therapies approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The bad news is, identifying which medication is best for each individual is a challenge and requires a trial-and-error period.

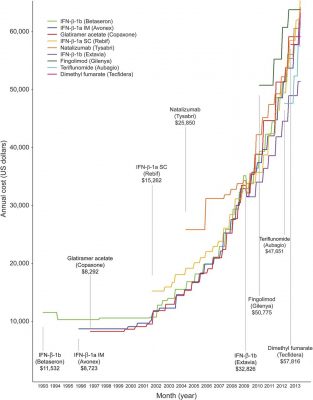

The ugly part: Although MS treatments have been shown to improve the quality of life, they are very expensive and are increasing in cost every year. In 2004 the average annual coast of MS treatments was between $8,000 and $11,000, but now that same medication can cost upwards of $60,000. Adding to the challenge is the fact that newer MS treatments are starting at 25 percent to 60 percent higher in cost than the pre-existing medications, and these costs in the U.S. alone are higher than other countries. One reason for the inflation of MS treatment costs is the current status of the U.S. health care system, which doesn’t place limitations on drug prices. A national health care system that can negotiate directly with pharmaceutical companies would impact the future of MS treatments, as well as the treatments of other medical conditions.

–Brittany Knight