This past school year, a group of UConn medical and dental students worked with students from the Weaver High School Culinary Arts Academy as part of a larger effort to prevent violence in schools. Damion Grasso, UConn Health assistant professor of psychiatry, is director of the program. Following is his account of the work this year’s group has done.

Are you a medical or dental student at UConn?

We could use your participation for the 2017-2018. Look for an information meeting in early September or contact us for more information.

The program is housed within the Department of Psychiatry and directed by Damion Grasso, PhD, a trained clinical psychologist and researcher in the area of childhood victimization and trauma.

For information about how to participate in the program please contact Dr. Grasso at dgrasso@uchc.edu.

The UConn Students Against Violence in Schools (SAVS) program engages UConn medical and dental students in advocacy work with middle and high-school students focused on promoting healthy relationships and preventing emotional, physical, and sexual violence among youth.

This year we partnered with a stellar team of 17 high school students at Weaver Culinary Arts Academy led by school social worker Yolanda Colon. Students were trained as peer ambassadors against violence by learning about:

- The types of violence experienced by youths,

- Adverse consequences of violence,

- The role of bystanders in preventing and addressing violent behavior,

- Steps to take when encountering violence, directly or indirectly, and

- School, local, and national resources for seeking help and guidance around these issues.

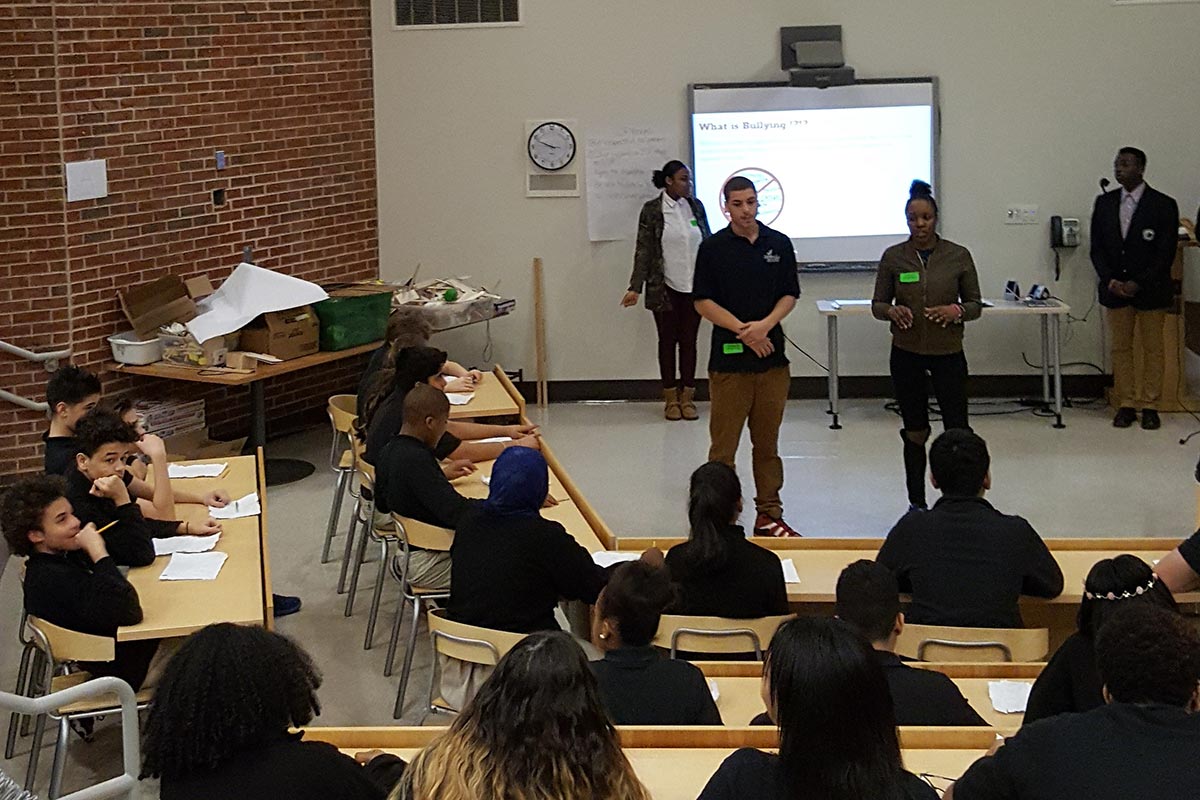

The Weaver students were then charged with working together to design and implement a project during the school year focused on one or more of these topic areas. The students chose to address issues related to bullying and designed a workshop curriculum, which they successfully implemented in five different Hartford-area middle schools throughout the year.

Weaver student leaders Kiara Hairston and Martin Barrows document the experience from the students’ perspective:

“We collaborated with UConn Health SAVS to make a difference in our school and the communities around us. Our project was about bringing this information to younger peers in middle schools where many of us were once students. We named our group ‘TAGZ’ and put together a presentation that emphasized the warning signs and effects of bullying. We originally planned on only giving one presentation, but teachers, administrators, and students were very impressed – and other schools contacted us to also do additional workshops. We ended up doing five this year.”

Students met on a regular basis with the UConn SAVS team and independently to do this work, which required a significant amount of effort.

When asked about her experience, group member Melicia Mendez commented, “This was a challenging task. Sometimes we were on the verge of giving up …but we kept pushing ourselves. In the end, it was worth it.”

“It was teamwork that helped us get through and make this program successful,” Martin said. “When it came time for them to give their presentations, I think we realized that we were not just trying to start a conversation about bullying, we were opening the door for younger students to take a stand for what they believe is right. We were encouraging these younger students to become positive role models to their peers and others.”

What makes this initiative so powerful is that these messages are coming from other youth and so are received somewhat differently than the same messages coming from adults and authority figures. Youth have a greater impact on their peers than they often realize. With this influence, they have a real opportunity to affect school climate. With empowerment, many will rise to the challenge, as did the students from Weaver Culinary Institute.

“Students need to understand the costs of bullying, especially kids who will be in high school soon. It feels good to be the ones to spread this message,” said student Malik Madric.

“I think we showed teachers and staff that we understand certain situations and are able to be mature about them and do our part in stopping violence,” said Pedro Velazquez, a junior at Weaver. “I myself have seen violence in my life and so I can relate. It feels good to be able to do what I can to stop it.”

After providing a presentation on the topic of bullying, the youth divided the attendees into smaller groups to discuss and role-play situational vignettes in which bystanders have an opportunity to address bullying behavior.

One of the vignettes addressed a student victimized because of his sexual orientation:

Dylan is a 9th grade student who openly identifies as gay. Over the summer, one of Dylan’s friends reports to the principal that other students from the high school have created a website that says, “Dylan is gay” and includes derogatory comments about Dylan. Dylan’s friend tells the principal that Dylan is now afraid to come back to school in the fall because the website includes threats to physically harm him.

Another vignette deals with the issue of racial bullying:

Mohamed, a Jordanian-American student interested in a career in engineering, is involved in a year-long mentoring/internship program where he spends afternoons at a local engineering firm. A couple of workers at the firm refer to him as a “terrorist” and “towel head” throughout the year. In February, Mohamed confides in one of his teachers about the conduct. Mohamed doesn’t want to “rock the boat” because he knows that this is one of the best mentoring opportunities offered by the high school. At the same time, Mohamed has now decided he no longer wants to go into engineering, drops out of college prep courses, and is performing less well in school.

Each small group was facilitated by one of the Weaver students, who guided the discussion and elicited from the group options for addressing the violence, aiding the victim, and preventing the behavior in the future.

In late May, we celebrated with the Weaver high school TAGZ team and honored them for their achievements. While some of the students will be graduating, returning students expressed high enthusiasm for continuing this work next year and recruiting students from the incoming class to participate. Ms. Colon, who worked closely with the students throughout the year, expressed pride in the students’ accomplishments and seemed eager to partner with the UConn SAVS team in the 2017-2018 school year.

UConn SAVS is also a valuable experience for the medical and dental students that volunteer to work with these high school students.

“Prior to matriculating at UConn for medical school, I served as a full-time tutor and assistant teacher at a charter high school in Boston,” said rising first-year medical student Desai Shyam. “SAVS helps to fill a void that is present in what I imagine are innumerable schools across the country by allowing for an open dialogue about the multiple forms of violence that can so easily percolate the lives of adolescents and youth, especially for those who live in underserved communities. I so valued the work we did because, though it involved a significant educational component, it put the majority of the thinking on the students. The students themselves generated ideas of how best to combat violence and bullying in their school communities, and they then took an admiral degree of initiative in putting those ideas into an actionable agenda. The students I worked with were surprisingly quick to open up regarding their own experiences, and as a future physician, it was both uplifting and formative to hear them speak so passionately about the urgency of bettering the mental and physical well-being of their peers.”

“The UConn SAVS Program formed a necessary relationship between UConnHealth and high school students at Weaver Culinary Arts Academy,” said second-year student Matt Lewin. “Bullying is a serious public health concern amongst adolescents, and I believe that empowering high school students to tackle this issue was a great initiative. I’m happy I had the chance to work with students who were unafraid to stand up against bullying. In the age of Facebook and social media, bullying will present itself in new ways both at school and in the home. With the help of Weaver students, I feel that a strong anti-bullying message and initiative was established and will leave a lasting impact amongst these students.”

“As I have had some background in education, and a passion for working with youth, I was pleased to find that there was a program at UConn where we could work with local students to help combat violence and bullying in schools,” said second-year student Kyle Shin. “With a changing technological landscape and the advent of social media, I think it is important to be able to present the experiences of those of us who have grown up immersed in that world. The interactive nature of the sessions and the ability to present a view different from the traditional teacher/authority figure provides a great way to shift the conversation and approach the problem from the students’ perspective.”

Violence within school communities is a serious problem with up to a third of students reporting some form of victimization by their peers (Hymel & Swearer, 2015). Victimization can come in many forms and has evolved with the advancement of digital technology.

Often, victimized youth experience more than one form of violence and can become overwhelmed with what may best be described as a culture of violence comprised of physical violence (e.g., shoving, pushing), as well as psychological forms such as verbal abuse (e.g., harassing, threatening), social exclusion and humiliation (e.g., spreading rumors), and what we refer to as cyberbullying – the use of social media, texting, and picture sending aimed at taunting, humiliating, and threatening peers.

Surely, exposure to violence can have dire consequences, including depression, anxiety, and traumatic stress, among other forms of impairment at home and school. Moreover, the adverse effects of peer victimization can extend well into adulthood (Lereya, Copeland, Costello, & Wolke, 2015).

A core element of promising programs to reduce youth violence is a focus on training bystanders to identify, help prevent, and effectively respond to peer victimization (Evans, Fraser, & Cotter, 2014).

Indeed, this is what UConn SAVS aims to do.

Are you a medical or dental student at UConn? We could use your participation for the 2017-2018. Look for an information meeting in early September or contact us for more information. The program is housed within the Department of Psychiatry and directed by Damion Grasso, PhD, a trained clinical psychologist and researcher in the area of childhood victimization and trauma. For information about how to participate in the program please contact Dr. Grasso at dgrasso@uchc.edu.

References Cited:

Evans, C. B., Fraser, M. W., & Cotter, K. L. (2014). The effectiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(5), 532-544.

Hymel, S., & Swearer, S. M. (2015). Four decades of research on school bullying: An introduction. The American psychologist, 70(4), 293-299. doi: 10.1037/a0038928

Lereya, S. T., Copeland, W. E., Costello, E. J., & Wolke, D. (2015). Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: two cohorts in two countries. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(6), 524-531.